|

|

|

|

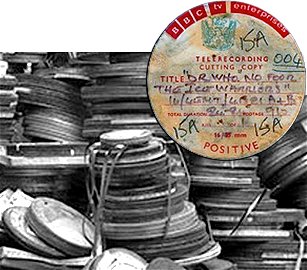

Prior to about 1978 many episodes

of programmes, or even complete series, are missing from television archives

as a result of destruction of unwanted film or a policy of 'wiping' expensive

magnetic recording tapes for re-use. It wasn't just the BBC that was responsible

for destroying large parts of their libraries although, as their archive

was the largest, the damage there was more considerable. ABC, ATV, Granada,

Southern and just about every television company in the UK disposed of thousands

of hours of recordings, and television records of historical and social

significance are now 'missing', probably never to be recovered. Once recordings had been transmitted, or sold on, they were of little financial or practical use to the television companies, other than being of 'historical interest', as the use of 'repeats' was not welcomed either by actors or 'performing rights' unions who argued that any significant re-use would adversely affect the livelihoods of the various staff required to make new TV productions. Although an agreement was eventually reached that allowed the broadcasting of a certain number of repeats a year, this had to be done within three years of the original showing or renegotiated on a 'case by case' basis. Some programmes and series, such as BBC's 'Maigret' and 'Sherlock Holmes', were also bound by individual contractual agreements to destroy any recordings after a certain date. The introduction of magnetic videotape in 1958 brought with it the huge advantage that it could be re-used. In the early 1960s the cost of a single tape was about £200, an expense that could be offset by its being re-used several times. However, the cost of producing a 35mm film negative and one print was about the same, so there was no real economic advantage in keeping programmes recorded on tape. 'Old' videotapes containing 405-line recordings were either scrapped or re-used for the new 625-line standard, therefore very few examples of 405-line recordings remain. Copies of both ITV and BBC recordings were difficult to obtain as most were either single film prints or videotapes and the cost of copying them for other archives was just an additional expense and difficulty. If a programme was archived for posterity, film was considered to be more durable than videotape therefore the majority of archived programmes exist as film recordings with the higher quality 35mm being the common standard for storage. With no outlet or use for 'old shows', many of which were in monochrome, television companies were finding it difficult to justify the expense of storage by the end of the Sixties, particularly with the increasing demand for colour productions. Not only that, but they were also running out of space and so they made the decision to dispose of any films more than three years old that were not considered to be of value in 'historical' terms. As a result, they started to categorise and assign 'grades to programme recordings according to their perceived historical value. |

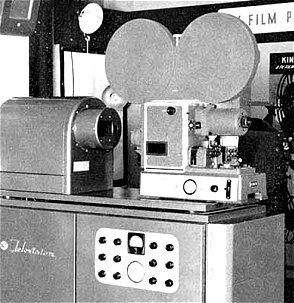

| Before the latter

part of 1958 the only practical way to 'record' a programme was by using

a technique called 'Kinescope' or 'Kine', also known as 'tele-recording'.

'Kinescope' can refer to either the process itself, a film made using this

process or the equipment used, essentially a 16mm or 35mm movie camera mounted

in front of a video monitor and synchronised with the monitor's scanning

rate. Only 35mm cinema film really had the required resolution and quality

to record the British 405-line standard. Until about autumn 1958 videotape recording was not available to the BBC or ITV so programmes were mostly broadcast live as the cost of recording television pictures on film was high and only the BBC and two of the early ITV companies used this method. 16mm film was also used, but mostly for making copies of programmes for overseas sales or internal use. The term 'Kinescope', coined by inventor Vladimir K. Zworykin in 1929, was originally used to refer to the cathode ray tube itself that was used in television receivers, so the recordings were referred to, in full, as 'kinescope films'. The General Electric laboratories in New York had experimented with making still and motion picture recordings of television images as early as 1931. The process was quite complicated as the time it took for the cathode ray scan to reach the screen had to be matched to the speed of each frame of film as it entered the camera's shutter gate, resulting in a negative of the broadcast being captured on film from which positive prints could be made and stored or distributed for use by other TV companies. In 1932 RCA was granted a trademark for the name, used for its cathode ray tube, but released the term into the public domain in 1950. Some 1930s recordings survive of live transmissions from the Nazi German television station 'Fernsehsender Paul Nipkow', the first public television station in the world, that were obtained by pointing a 35mm camera at a receiver's screen but most surviving Nazi 'live' programs, such as those made of the 1936 Olympic Games, were shot on 35mm first and then transmitted as a television signal (with about a two minute delay from the original event) from an outside broadcast van on the site using a process called 'Zwischenfilmverfahren'. There is some suggestion that the BBC itself may have experimented with filming the output of television monitors before its television service was suspended in 1939, at the start of World War II, but no documented evidence supports this. In September 1947 Eastman Kodak, in co-operation with NBC and DuMont Laboratories, introduced the 'Eastman Television Recording Camera' for capturing images from a television screen under the trademark name of 'Kinephoto'. A 'home tele-recording kit' was apparently introduced in Britain during the 1950s, allowing enthusiasts to make their own 16mm film recordings of television programmes. Apart from the short duration, the other major disadvantage was that a large frame had to be positioned in front of the television set to block any stray light reflections and making it impossible to watch the set normally during the filming. It is not known if any recordings made using this equipment still exist. NBC began making colour 'kines' of some programmes in September 1956, using a lenticular film process which, unlike colour negative film, could be processed rapidly. |

Early RCA Kinescope machine |

PA-302 General Precision Laboratories (GPL) kinescope (c.1950-1955) |

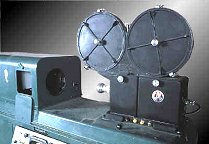

'Tele-recording' became much

more widely used during the 1950s and 1960s and this technique was used

for both archiving and syndicating shows, although the quality was often

poor because it captured an image from a 2D display. This growth in the

practice created the need for archive library facilities to be provided

to store the growing collections of large cans of film. Essentially, these

were large storage warehouses fitted with expensive air-conditioning systems

that maintained the constant temperature of 55ºF needed to prevent deterioration

of the films.

Up until the early 1960s the bulk of British television's output was broadcast live with tele-recordings being used to preserve programmes for repeat showings that had previously required the entire production being performed live for a second time. British broadcasters continued the use of tele-recordings for domestic transmission well into the 1960s, with 35mm being the gauge mostly used as it produced a higher quality result. For overseas sales cheaper 16mm film was often used. Although the system was mainly used for black and white reproduction, some colour tele-recordings were made but they were much less common as, by the time colour programmes became widely used, videotape conversion was easier, of higher quality and much reduced in price. Domestic UK use of tele-recording for repeat broadcasts was reduced dramatically after the move to colour in the late 1960s but 16 mm black and white film tele-recordings were still being offered for sale by British broadcasters well into the 1970s. Before videotape became the preferred transmission format during the 1980s, colour video recordings used in programmes were still often transferred onto film. Videotape and 'Double System' Editing |

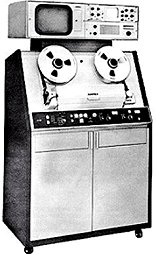

| In 1951 Bing Crosby

Enterprises produced the first experimental magnetic video recordings although

poor picture quality and high tape speed rendered it impractical to use.

Their equipment used a one-inch tape running at 100 inches per second which

meant that a reel three feet in diameter held about fifteen minutes of video.

RCA also demonstrated a system in 1953 that recorded in both monochrome

and colour but the tape speed was even greater, 360 inches per second (about

20 miles per hour), making it nearly impossible to produce a stable picture.

The recording time was only four minutes and RCA were planning to use 19-inch

reels to increase this to 15 minutes on 1/2-inch tape for colour and 1/4-inch

tape for monochrome. Ampex introduced their first commercial 'Quadruplex' videotape recorder (VTR) in 1956, followed by a colour version in 1958, delivering high quality and instant playback at a much lower cost. The first machine was about twice the size of a washing machine and used four spinning video heads rotating at 14,400 revolutions per minute, each head recording one part of a tape that was two inches wide. Ray Dolby, later famous for his tape noise reduction process, was one of the engineers involved in the project. 'Quadruplex' tape started to replace 'kinescope' as the preferred means of preserving television broadcasts and, by the late 1950s, VTRs were already being used for 'time-shifting' purposes but, as far as the recording of entire programmes was concerned, the lack of a simple editing capability was still a problem. Although the first completely video-recorded show went out on CBS in 1958, programmes were still primarily 'recorded live' as editing and splicing was only possible by 'developing' the magnetic pattern on the tape and cutting between frames. Video would not become more easily editable until the late 1960s. Editing with timecode was introduced in 1967 with 'edit pulses' added to the control track on the tape to make these points more obvious but this resulted in half a second of audio being lost at the edit point, requiring the audio to be re-laid from a second machine. The first computerised editing systems only began to appear in the early 1970s. An alternative technique was invented that involved wrapping the tape around a large drum containing heads that rotated against the tape to produce a helical scan, the approach that eventually became the standard. This system was used in the production of the first consumer video recorders, such as the 1964 Philips semi-pro EL3400 open reel recorder, and in the development of smaller and lighter 'portable' units such as the Sony 'Portapak'. Cassette-based recorders (VCR) followed in 1971 with the introduction of Sony's 3/4in 'U-Matic' recorder that was intended for home use but was popularly utilised by corporate audio-visual departments and some television companies. The Philips N1500 videocassette recorder of 1973 produced extremely good quality recordings on a 60-minute VC60 cassette. Even after the introduction of 'Quadruplex' television companies continued to use 'kinescopes' in the 'double system' method of videotape editing. As it was not possible to slow down or freeze-frame a videotape at that time, the unedited tape would be copied by kinescope and edited as a film. This technique was used for the American 'Rowan and Martin's Laugh-In' series. |

Ampex VR1200B recorder, late 60s |

1964 Philips EL3400 |

Over the years, many attempts

had been made to take television images and convert them to film via 'kinescope'

at a high enough quality to then project them onto the 'big screen' in

cinemas. In the mid-1960s H. William Sargent Jr. used modified high-band

'Quadruplex' VTRs to record from conventional analogue 'Orthicon' video

camera tube units using the monochrome 819-line interlaced 25fps French

video standard.

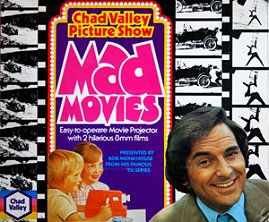

Image quality was much improved and, by the capture of more than 800 lines of resolution at 25fps, the tapes could be converted to film via 'kinescope' recording with sufficient resolution for cinema use. Calling it 'Electronovision', he gave the impression that this was a brand new system, using a high-tech name to distinguish it from the more 'conventional' process. 'Missing' Programmes A famous 1970s court case in which Bob Monkhouse successfully defended his right to hold and own 'copyrighted' material if only used privately for his own entertainment, and not for profit or gain, set a legal precedent by clarifying a 'grey area' in copyright law and effectively allowing anyone to make recordings of anything shown on television without fear of prosecution. This 'amnesty' now opened up huge possibilities as a new source of recovering 'lost' material and, over the subsequent years, many programmes and episodes thought to be 'lost' forever, particularly those made by the BBC, have been returned as tele-recordings by foreign broadcasters or private collectors - more than 2,000 in the last 20 years. Another source proved to be production staff who kept examples of their own work or took home prints that were marked for destruction. Some prints, made for export on 16mm, also found their way into private film collections, often with their main or end titles removed to make them commercially worthless. In 1993 the British Film Institute launched an initiative called 'Missing, Believed Wiped', designed to raise the public awareness for recovering 'lost' recordings. Since then, a lot of returned material has been given to the National Film and Television Archive who usually make copies of the material before returning the original to the donor. |

| The BFI National

Archive is the most significant collection of TV and film recordings in

the world and they are always keen to hear from people who think they may

be in possession of 'missing' British television material. They frequently

publish a list of the twenty current most important 'missing' programmes

and also hold annual 'Missing, Believed Wiped' events at their London South

Bank location. If any member of the public thinks they have a full episode,

clips or behind-the-scenes footage from a missing TV series they should

contact Dick Fiddy at the BFI (dick.fiddy@bfi.org.uk). It is now possible 'restore' colour to some monochrome tele-recordings that were originally made in colour. The idea came from James Insell, a preservation specialist at the BBC's Windmill Road archives centre in West London who explains: "I first thought of the idea of colour recovery about 1994.... I was watching a black and white Jon Pertwee (Doctor Who) episode on UK Gold. On the end titles I could see some red breaking through. 'Where is this coming from?' I thought. 'How is there colour coming out of this black and white film recording?'". What he saw were minute electronic artifacts burnt into the film when the black and white telerecording was made, a kind of 'ghost' of the original colour. They take the form of a faint pattern of 'chroma-dots' across the picture that provide the key to colour recovery. Practical application of this came after the development of software created by Richard Russell who had helped develop the BBC microcomputer in the 1980s. In recent years, the BBC has also introduced a video process called VidFIRE that can be used to restore 'kinescope' recordings to their original frame rate by interpolating video fields between the film frames. |

|

|

|

All

Original Material Copyright SixtiesCity

Other individual owner copyrights may apply to Photographic Images |