|

|

|

As with

78s, the speed led to their commonly being known as '45s'. The 1970's saw

the development of the 45 rpm 12" single which utilised the larger diameter

and increased speed to provide higher audio quality. Approximate playing times

for the various sizes and speeds are: 12" 331/3

rpm (LP) 22 minutes,

12" 45 rpm (12" Single) 15 minutes, 12" 78 rpm 5 minutes, 7"

331/3 rpm (EP) 7 minutes, 7" 45 rpm (Single) 5

minutes, 10" 331/3 rpm 15 minutes, 10" 45

rpm 12 minutes and 10" 78 rpm 3 minutes. A speed of 162/3

rpm was sometimes used for 12" discs that required an exceptionally

long playing time. The classic LP album, at 331/3 rpm,

offers a good balance between audio quality and playing time. These numbers

are not absolute, just a general guideline.

There is an area about 6mm (0.25") wide at the outer edge of the disc,

called the lead-in, where the groove is widely spaced and silent. This area

allows the stylus to be lowered at the start of the record without damaging

the recorded section of the groove. Between each track on an LP or EP record

there is usually a clearly visible short gap of around 1mm (0.04") where the

groove is comparatively widely spaced, making it easier to find a particular

track on the record. Towards the label at the centre, at the end of the groove,

there is another wide-pitched section known variously as the 'lead-out', the

'run-out' or 'dead wax'. At the very end of this section the groove joins

itself to form a circle called the 'lock groove'. When the stylus reaches

this point it circles repeatedly until lifted from the record. Although generally

silent it is, of course, possible to produce sound within the lock groove.

Probably the most famous example of this is on The Beatles' Sergeant Pepper

LP where there are, in fact. three different versions depending on which release

of the record you listen to!

In

1958 the first stereo two-channel records were issued by Audio Fidelity in

the USA and Pye in Britain, using the Westrex '45/45' single-groove system.

Several record companies, including RCA and Decca, adapted the LP record for

stereo playback, using the two-in-one technology pioneered in the 1930s, where

each wall of the groove held one of the channels. Some early Sixties EPs had

both a mono and stereo release but, as a rule, singles were in mono up to

around 1970 when production of mono records ceased. Most UK singles went over

to stereo during 1970. David Bowie's 'Space Oddity' on Philips Records in

1969 was an early mono and stereo single but most were still in mono early

in 1970. Philips and their Fontana label UK singles were actually denoted

as 'mono' in a box on the right hand side from around 1966 up to 1969, although

later releases did not actually state 'stereo' even though they were. The

identifying point was the small matrix number initial figures of either 7x

for mono or 7y for stereo.Already

affected by sales of cassette tapes, the arrival of the compact disc (CD)

in the 1980s severely curbed production of LP and 45 discs. Sales of both

dropped quickly and most major label record companies stopped releasing them

in large amounts by the early 1990s.

|

An

oddity worth briefly mentioning, if only for the sake of nostalgia, are

'Flexi-Disc' records that were introduced in about 1962 and often given

away by music magazines or as promotional items for various products.

These were made of a thin, flexible vinyl sheet, often containing exclusive

tracks or popular hits, and are quite popular as collectables. The quality wasn’t great due to the groove depth in the thin vinyl, neither did they tend to survive very long as they were quite fragile. Often, a coin had to be used to weigh the disc down to stop it sliding around on the turntable! These were also known as phonosheets (trademarks included Sonosheet and Soundsheet). The Beatles used to make Christmas records in this material to distribute to fan club members. |

|

|

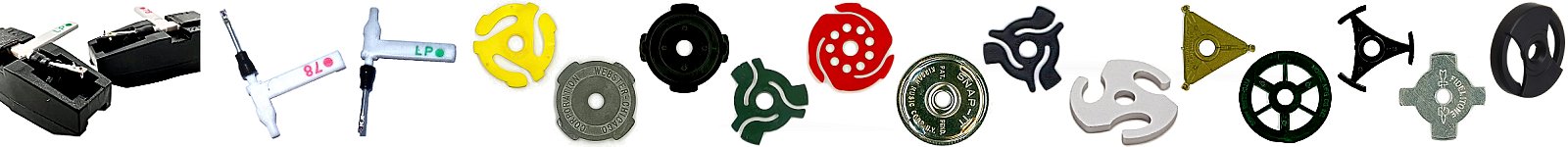

Note on measurements: 1 mil is equal to .001 inches or one thousandth

of an inch. The measurements of stylus tip radius and groove width are also

often given in 'microns', short for micrometer (symbol: µm), where 1 micron

is equal to .001 millimeters or one millionth of a meter. 1 mil = 25 µm and

0.7 mils = 18 µm.

SOUND QUALITY and PRODUCTION

The making of a vinyl record is a more laborious process than you might think,

for a simple piece of plastic. There are machines to cut studio recordings

into a master version of the audio disc, then another set to create a metal

negative plate of the master ready for the largest machine, the record press

itself, which will produce many vinyl copies. Innovations in manufacturing

techniques and equipment within the record production industry moved at a

very fast pace during the late Fifties and Sixties but essentially, in simple

terms, this was how a vinyl record was produced during that period.

Before

even starting to produce a record there are points to consider as vinyl has

a number of inherent qualities that affect the design and cutting process.

A vinyl record has considerably less dynamic range than a digital recording

and cannot reproduce

as broad a range in frequency, so excessive high or low end can cause distortion

in the groove. It will also sound distorted if the

sound mastering engineer tries to make the record too loud. Large dynamic

swings can cause the stylus to jump when the record is played on a consumer’s

turntable. In addition, the higher the volume amplitude the wider the grooves

need to be, which means less playing time per side. The louder the source

recording, and the more bass, the greater the lateral movement of the cutting

stylus and hence the width of the groove itself. The amount of music a record

can hold is limited and the gap between the grooves is determined by the playing

time.

The turntable stylus will eventually reach the end of a side, so the artist

and producer need to consider the time factor when creating the song running

order and deciding which songs will go on which side of the record. It is

possible to extend the playing time by reducing the volume and attenuating

the bass but this also reduces the quality. The higher speed of 45 rpm provides

more definition in the high frequency spectrum than 331/3

rpm as there is more of the groove to hold each second of audio while 331/3

rpm allows longer cuts and deeper low-end within certain limits. Effectively

the standard 12" LP album at 331/3 rpm is a compromise

between the sound quality and the playing time. The 45rpm 12" single developed

in the 1970's has only one track per side to get the maximum dynamics and

quality available.

The closer the stylus gets to the centre of the disc, the smaller the circumference

of the groove becomes. On the outer edge of a 12" LP the stylus moves

at approximately 20 inches per second but near the label it only moves at

approximately 8.5 inches per second. With less

groove length per second of music the resolution gets diminished.

In digital

audio terms this is equivalent to reducing the sampling rate of a recording

from 96 kHz to 22.05 kHz, quite a large difference in fidelity. This has to

be taken into account when choosing the song order, knowing that the ones

on the inner parts of the disc won’t sound quite as clear and crisp.

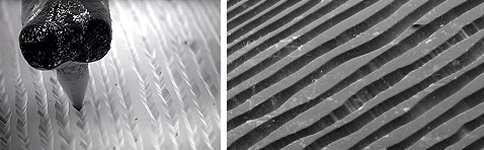

THE GROOVE

The normal commercial disc is engraved with two sound bearing concentric spiral

grooves, one on each side of the disc, running from the outside edge towards

the centre. The recording is played back by rotating the disc clockwise at

a constant rotational speed with a stylus (needle) placed in the groove, converting

the vibrations of the stylus into an electric signal via a magnetic cartridge

and sending this signal through an amplifier to loudspeakers.

|

The

groove itself is actually V-shaped and each side of the groove 'wall'

carries one of the stereo signals. The right channel is carried by the

side closest to the outside of the record and the left is carried by the

inside wall. The frequency and amplitude (volume) information are determined

by the width and depth of the groove. If there is too much bass, a stylus

could literally jump out of the groove! It’s the job of the mastering

engineer to get it just right when doing the transfer to vinyl. Record players are electromagnetic devices that convert the vibrations encoded in the grooves of the vinyl into electrical signals. The record is placed on a turntable, which is a circular plate usually covered with rubber to prevent scratching. The turntable then rotates via a belt or direct drive system to spin the record at a set speed of 331/3, 45 or 78 rpm. The actual transformation of energy into sound is the job of the magnetic cartridge, to which is attached a stylus — a needle made of a hard substance like a small piece of sapphire or industrial diamond. These sit on the end of a tone arm mounted on the record player and, as the record spins, the tone arm follows the groove and spirals inward. As it does so, the stylus 'rides' in the groove carved in the vinyl, which carries the amplitude and frequency of the audio, as well as the left and right stereo information. |

The vibrations picked up by the stylus travel to the magnetic cartridge where

they are converted to an electrical signal. Cartridges come in two types:

moving magnet (MM) and moving coil (MC), each of which have slightly different

output levels. A receiver/amplifier increases the electrical signals generated

by the cartridge to the level necessary to drive loudspeakers and/or headphones.

The depth of a vinyl record groove is nominally 28µm (0.0011"). The bottom

of the groove is not, in fact, a sharp corner but has a radius of 6µm or (0.00025").

How many grooves are there on a record? Only 2 - one on each side! An LP typically

contains 18 to 22 minutes of music per side.

For a 20 minute long side, the spiral groove is around 1400 feet long (467

yards) and consists of 667 threads. 2.23 seconds of audio is stored per square

centimeter. A 45rpm record groove is about 100 feet (33.3 yards). Measurements

are affected by the distance between the grooves and the playing length of

the record.

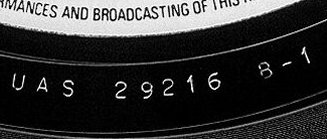

| THE

CUTTING Once the mastering engineer is satisfied that all the tracks sound as good as possible a master disc is created, also known as a 'lacquer master', and is an aluminum plate onto which a layer of molten 'wax' is spread in a sealed, dustproof, temperature controlled and air conditioned room. The wax is heated and spread on the plate until smooth, then cooled slowly to produce a perfectly flat and blemish-free surface. Early versions of master discs were made in soft wax before a harder lacquer started being used. After being examined for defects, it is transferred to a recording room where an operation known as 'lathe-cutting' is used to create the master audio disc. Originally sound was recorded directly onto the master disc (also called the 'matrix') at the recording studio. From about 1950 onwards it became the more usual practice to have the performance first recorded on an audio tape which could then be processed, and/or edited, before being dubbed on to the master disc. A special cutting lathe is used to produce the sound groove. This is a machine fitted with a cutting head that contains a tiny stylus usually made of sapphire. Where a record player turntable and cartridge converts the groove on a record into sound, the electronics in the cutting lathe do the reverse. They electrically turn the sound waves into vibrations that the lathe’s stylus cuts into grooves on the master disc. |

|

|

During

this process the stylus gets so hot that it has to be cooled with helium

gas to avoid a fire. While the stylus moves horizontally when reproducing

a mono disc recording, on stereo records the stylus moves at an angle

as well as horizontally. In the Westrex system, each sound channel drives

the cutting head at a 45 degree angle to the vertical. During playback

the combined signal is sensed by a left channel coil mounted diagonally

opposite the inner side of the groove, and a right channel coil mounted

diagonally opposite the outer side of the groove. The cutting engineer has to manually allow for the changes in sound which affects how wide the space for the groove needs to be on each rotation. Also, because the cutting is done in real time as the music is playing, when making a LP master the operator has to manually create the spaces between songs. This is accomplished by scrolling the stylus very slightly toward the centre of the record to create a visible gap. The catalogue number and stamp identifying code, to distinguish each master, is written or stamped onto the unused space in the lead-out on the master disc, producing visible recessed writing on the final version of the record. The 'history' of any vinyl record can be traced through the numbering and lettering found on the record lead-out area. Sometimes an engineer will also 'sign' their work or leave a comment, often cryptic or humorous, in this area. |

The stamper code is raised (slightly projects) from the surface of the disc

whereas the lacquer or mother code are set into the vinyl. This is because

the stamper code was punched or scratched into the negative of the disc, whereas

the mother number or code was punched or scratched into the positive copy.

The mother code is usually written as a number and is easy to understand.

The stamper code, particularly on British records, is often a letter, or group

of letters. All record companies and pressing plants had their own systems

for this so you would need to know the convention used to know what these

codes mean. An example of this is that Decca used the word ‘BUCKINGHAM’ for

the code used for the numbering of the stamper. The first stamper to be made

from the mother has the letter B, the next has U and so on. Therefore B=1,

U=2, C=3, K=4, I=5, N=6, G=7, H=8, A=9 and M=0 or 10. Stamper 66 from mother

7 doesn't necessarily mean that there were a previous 65 stampers made from

mother 7 as stampers were numbered sequentially as they were used for production,

so stampers 1 to 10 may have been made from mother 1, stampers 11 to 20 made

from mother 2, and so on.

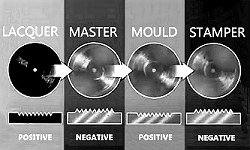

MAKING THE MASTERS AND STAMPERS

After cutting, the lacquer master is washed with nitrogen and put into a chamber

where it is finely electroplated, sometimes with silver or gold, completely

coating it and providing a metallic base for further plating operations. This

and all subsequent metal copies are known as 'matrices'. In order to strengthen

it, the master disc is then put into a solution of copper sulphate where a

high electrical charge transfers copper from the solution onto the disc, a

process called 'electrolysis'. The copper-plated disc is put into a further

bath where the coating is thickened. These processes cover the master very

precisely so that all the 'sound grooves' are perfectly coated. The

resulting layer of metal is then stripped away from the lacquer master, through

careful cleaning processes, providing a 'negative master' that it is a negative

copy of the lacquered surface, with ridges instead of grooves.

The negative master is still not strong enough to be used in the production

process so another, more robust, disc called the 'mother matrix' must be made.

In the early days the negative master itself was used as a mould to press

records for retail sale, but as the demand for higher production levels grew,

another step was added to the process where the negative master is coated

with a fine separation solution and electroplated with copper and nickel to

create metal positive matrices, or 'mother discs'. As the negative master

is the unique source of the positive, made to produce the negative 'stampers',

it is considered a 'library' item.

|

|

Copy positives, needed to replace worn ones, are made from unused early

stampers. These are known as 'copy shells' and are the physical equivalent

of the original positive. From these positives, negative stampers are

created which, in addition to the copper, will receive coatings of nickel

and chromium to make them strong enough to be used in hydraulic presses

to mould the vinyl discs. The positive master disc is carefully washed,

as it is critical to avoid any dust contamination, and carefully checked

for any defects. It is then sprayed with a separation coating and submerged

in copper and nickel baths where it is electroplated in layers. The electroplated master then gets pulled apart, creating two discs that are mirror images of each other. One is the original positive master with grooves and the other is its opposite, with ridges instead of grooves. The latter is called the 'father' disc and is what is used as a stamper for pressing the record. The creation of multiple stampers provides the ability to make a large number of records quickly by using multiple pressing machines. The stamper is strengthened further by attaching it to a backing plate using a thermal pressure process. It is now ready for the central hole to be precisely positioned and drilled, where a magnifier is used to view the grooves to ensure exact alignment. The disc is then given a final polishing to ensure removal of any dust particles that could cause sound defects. Once the stamper is produced, the pressing plant can begin to make vinyl copies. One stamper is required for every thousand or so records. After that, the stamper starts to wear out and the audio quality begins to deteriorate. Additional replacement copies of the stamper can be made by electroplating and splitting the original positive mother disc. |

|

|

MOULDING THE DISC The majority of music records are pressed in black vinyl. The material used to colour the transparent vinyl plastic mix is carbon black, a generic name for the finely sized carbon particles produced by the incomplete burning of a mineral oil-based hydrocarbon. Carbon black also increases the strength of the disc. The vinyl used in making records is produced in large quantities in a special mixer and starts out as a fine powder of ingredients including shellac, resin, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and as many as 18 other substances, weighed in precise amounts. A great number of vinyl records are pressed on recycled vinyl. New 'virgin' or 'heavy' vinyl (180-220 g/m˛) is most often used for modern 'audiophile' releases as the sound quality and durability of a vinyl record is highly dependent on the quality of the vinyl. During the early 1970s, as a cost-cutting move, much of the industry adopted the technique of reducing the thickness and quality of vinyl used in mass-market manufacturing, producing lighter and more flexible pressings. This was marketed by RCA Victor as the 'Dynaflex' (125 g/m˛) process but was considered inferior by most record collectors. |

|

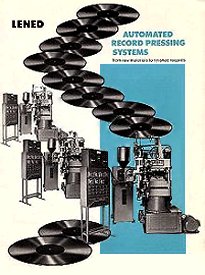

The

mixture is heated to melting point inside the mixer, stirred and beaten

until it achieves a dough-like consistency, then placed onto rollers where

it is transformed into a long flat sheet. On exit from the machine the

strip is cut into small pieces called 'biscuits' (each one the right size

to make one record) or, in some cases, vinyl pellets. Pellets or biscuits

get loaded into a hopper on the record press and are melted and shaped

into a blob of vinyl known as a 'pattie'. A record press is the machine used for manufacturing vinyl records. These large machines, some made by long-forgotten companies like Lened, SMT and Toolex, churned out the massive stream of vinyl discs demanded by the post-war music industry boom. When compact discs (CDs) appeared in the mid-1980s, most of these now ageing vinyl record presses ended up in junkyards or warehouses. Only recently have new custom-made machines been produced. Most machines in use today were made in the 60s and 70s and are essentially a heated hydraulic press with a closing force of about 100 tons and fitted with the negative stampers. Stampers (one for side A and one for side B) for the title to be pressed are fitted to the moulds. The record labels and a pre-heated pattie are placed in the mould cavity while the moulds are being heated by steam at a pressure of 140-170psi. The labels that go in the centre of each side of the disc get loaded between the biscuit and the stamper on each side. There are no adhesives on the labels - they are baked in advance to get all the moisture out of them so they don’t bubble when pressed onto the vinyl, then they are fused into the record by heat and pressure, so there is no point in trying to remove them, even if you wanted to. When the pressing sequence starts, the mould closes, heating the pattie and labels to about 300 degrees F. and squeezing them with roughly 100 tons of pressure (2,000 psi). The pattie flattens out and, through the process of compression moulding, the material fills the cavity and takes the form of the finished product, complete with the grooves formed by the negative stamper and the labels fused into their respective spots in the centre. In the mid-60s, Emory Cook developed a system of record forming where the mould pressure was replaced by a vacuum. In this technique, the mould cavity was evacuated and vinyl was introduced in micro-particle form. The particles were then flash-fused instantaneously at a high temperature forming a coherent solid. Cook called this disc manufacturing technology 'microfusion'. A small pressing plant in Hollywood USA also employed a similar system which they maintained fused the particles more evenly throughout the disc thickness, calling their product 'Polymax'. Both claimed the resulting disc grooves exhibited less surface noise and greater resistance to deformation from stylus tip inertia than conventional pressure-moulded vinyl discs. When auto-changing turntables were commonplace, records were typically pressed with a raised (and ridged) outer edge to the label area. This reduced the risk of damage to the delicate audio grooves by allowing records to be stacked onto each other, gripping each other, without the playing areas coming into contact. Auto changing turntables included a mechanism to support a stack of several records above the turntable itself, dropping them one at a time onto the active turntable to be played in order. |

|

When

the moulding process has taken place, water (at a pressure equal to the

steam pressure) is admitted to the moulds which both expels the steam

and cools the moulding down to a temperature where the vinyl disc will

be stable. The machine then opens, the disc removed and the excess vinyl

on the edge trimmed for re-use, after which the discs are stacked onto

a spindle and allowed to cool. The pressing time for a 7" disc is about 15 seconds and 25 seconds for a 12". Periodic 'listening' tests are carried out on the finished items to ensure consistent quality. Before shipping the vinyl records out, the plant makes a few test pressings that they send to the artist and record label for appraisal. This is usually done on a press used specifically for that purpose and not a production press and the samples produced generally have monotone or white labels, with a large 'A' (advance release copy) printed on them. Once they are approved, all the copies ordered are produced on production machines. In the case of LPs, the artwork for the record sleeve has normally already been designed, approved and printed at this point. |

|

HANDLING

AND STORAGE To preserve the condition of your vinyl records it is important to avoid touching the playing surface of the record with your fingers. Your skin produces natural oils which can be transferred to, and accumulate on, the record's surface over time, leading to surface noise. Hold the record with contact on the label and outer edge only, to maintain its long-term playability. Stacking vinyl records for any length of time should be avoided. Stacking records can gradually lead to warping so they should always be kept vertically, like books, and away from heat sources. Storing records without their sleeves will very quickly lead to scuff marks and scratches that will permanantly damage the sound quality. |

FURTHER

INFORMATION: ![]() How to Clean Your Record Collection

How to Clean Your Record Collection ![]() Secrets From the Dead Wax

Secrets From the Dead Wax ![]() Pre-Vinyl

78rpm Records

Pre-Vinyl

78rpm Records ![]() Sgt Pepper's Inner Groove

Sgt Pepper's Inner Groove ![]() Sixties Manufacturing Process

Sixties Manufacturing Process ![]() British Record Charts

British Record Charts

|

|

All

Original Material Copyright SixtiesCity

Other individual owner copyrights may apply to Photographic Images |