|

|

|

| The King's Road,

or Kings Road, is a major London thoroughfare, just under two miles long,

that runs from Sloane Square in the east (on the border with Belgravia and

Knightsbridge) and through the Moore Park estate on the border of Chelsea

and Fulham by Stamford Bridge. Shortly after the Stanley Bridge it takes

a turn at the junction with Waterford Road, in Fulham, where it then becomes

New King's Road and continues on to Putney Bridge before reaching its western

end in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. Interestingly, Kings

Road street signs apparently have an apostrophe in the SW10 and SW3 postal

districts but no apostrophe in SW6. The first known recorded instance of the area being mentioned by name was in about 785, when Pope Adrian sent legates to England for the purpose of reforming the religion and the Anglo-Saxon chronicles of the Mercian king Offa named it as 'Chelcehithe' and 'Cealchythe'. Twenty years after the Norman conquest of 1066 the Domesday Book recorded that the 'Manor of Chelsea' (covering 780 acres of meadow, pastureland and woodland, with 60 pigs) was valued at nine pounds. The actual name 'Chelsea' only began to be used in the early part of the 18th century. During the 16th and 17th centuries it was known as 'Chelsey' and, before then, as 'Chelceth' or 'Chelchith'. It remained fairly rural for the next 500 years and it was not until the arrival of King Henry VIII's advisor, Sir Thomas More, who bought more than 20 acres of land around what is now Beaufort Street in the 1520s and built a house there, that its profile was raised. Large mansions started to dominate the North bank of the Thames during the 16th and 17th centuries. Before the 16th century the road was only a rural track that ran along the south side of Chelsea Common and was mainly used by farmers. In 1536 Henry VIII was the first monarch to use the 'Kings Road' when, after building his own manor house on the site where 19 - 26 Cheyne Walk is today (and which is where Princess Elizabeth, Lady Jane Grey and Anne of Cleves lived at various times), it was used exclusively by him to travel to and from the house and became 'the king's private road'. The image on the right shows the The King's Road in 1820, from a watercolour by William P. Sherlock |

|

|

The Kings Road remained a royal

'private' road for over a century and Charles II (1630 - 1685) used it to

travel to Kew. It was he who had the un-surfaced track gravelled and converted

into a proper carriageway connecting his palaces at Hampton Court and Whitehall

(with the additional advantage of it passing close by Sands Manor, which

was the home of his mistress Nell Gwynne). By 1694 the Chelsea area, once described as a 'village of palaces', was a popular location for the wealthy. Although it had a population of about 3,000 it was still mainly rural and generally served as a 'market garden' for the city, a situation which more or less continued until the wave of urban expansion during the 19th-century saw major building development. At that time, the area surrounding the World's End tavern was nurseries and farmland with the tavern providing a central leisure facility and a safe haven for travellers. Generally, travel via the river was preferable as the area called 'Five Fields' (between Chelsea and Knightsbridge) was notorious for robberies. It was notorious for the activities of footpads and robbers and, in the 18th century, the Earl of Peterborough was stopped in it by highwaymen. Royal Avenue is a broad avenue with a road down each side laid out by Sir Christopher Wren in 1682 as part of a planned direct route from the Royal Hospital to Kensington Palace. King Charles II, the sponsor, died in 1685 and so the work was never completed. Enclosed by a hedge and a white fence, it was known as White Stile Walk by 1748. In 1711 the Kings Road was controlled by six gates, preventing others from easily using the road. Sir Hans Sloane bought the Manor of Chelsea in 1712 and when George I tried to take away all access rights to the road it was he and the local rector who organised a petition and saved the custom. It remained 'open' and by 1719 three toll houses had been built and the road was open to certain 'privileged' people. The use of special copper 'pass' tokens that had one side stamped 'The King's Private Road' (leading to its shortened 'modern' name) and the other with the King's monogram was established by 1722. There were at least four types of these and examples can today be seen embedded in the pavement at Duke of York Square. By the 1780s it was open to nearly everybody and around the turn of the century the royal family of George III is known to have regularly travelled it, stopping at Blacklands Farm (part of which is now Chelsea Common) 'to take milk'. 'The King's Road' did not become a thoroughfare for 'general' traffic until the reign of George IV, in 1820, when ownership of the road passed from the Crown to the Parish and the road was considerably widened in the 1860s. By 1836 there were houses along the road near World's End and Baron de Berenger had opened his National Sporting Club in the grounds of Cremorne House. When the first Ordnance Survey map was produced thirty years later, the tavern was shown as being surrounded by housing and the Sporting Club had become the Cremorne pleasure gardens. By 1894 the Pleasure Gardens had been replaced by streets and housing, hardly any of which survive today as the area was cleared between 1969 and 1975 to construct the World's End estate that was, at the time, the largest council housing estate in Europe. |

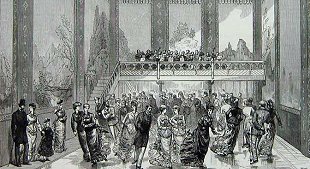

| The Glaciarium, a

sophisticated artificial rink created by using technology invented to freeze

meat for transport, was opened at 279 Kings Road by John Gamgee in March

1876. This was replaced by the Palaseum in 1910 as variety theatre popularity

increased and there were a number of entertainment theatres along the road

at this time. The now-disused Lots Road coal and oil-fired power station

on the bank of the River Thames was built in 1905 to provide electricity

for London's expanding underground transport system. At the time it was

the largest power station in the world and preceded the Battersea power

station by 25 years. Such was the western expansion of the urban capital

that by 1929 the Chelsea area, largely rural just a century previously,

had one of the smallest proportions of public open space - just 13 acres

(about 2%). Chelsea's historical occupation by the more artistic and Bohemian elements of London's society became increasingly overt and flamboyant after the recovery from the ravages of WWII started to take effect, in much the same way as Soho, with the youth of the day having much more disposable income and the 'nouveau riche' of the pop/rock music world carrying the twin 'gospels' of lifestyle and fashion to the masses. The road and surrounding areas have been the subject of much demolition and refurbishment since the late Fifties when Chelsea Borough Council started to undertake major new social housing projects, particularly the construction of the Cremorne Estate which was named after the historical Cremorne Gardens that once occupied the site. The World's End area, that still showed some ravages of the bad damage it had suffered during the war, was also completely redeveloped between 1967 and 77 with the red brick structures that heralded the destruction of so many of the remaining Victorian terraced houses. |

The Glaciarium: Illustrated London News, May 1876 |

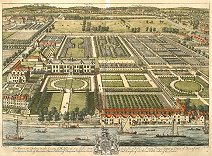

Beaufort House and gardens |

Adjacent to the Glaciarium

was the site of Beaufort House, home of Sir Thomas More. The ground was

purchased from the Sloane Estate by Leader of Moravians Count Nicholas Ludwig

von Zinzendorf in 1751 and the Moravian burial-ground was established there.

The part actually used for interments is now fenced in and closed. Moravians

were devout refugees from Bavaria and the Moravian Church Fetter Lane congregation

was founded in the City of London in 1742 by members who had come in search

of passage to the British colonies in the Caribbean for missionary work

among the slaves. The Fetter Lane chapel was destroyed by bombs in 1941 and, after a period of incongruity, it was decided to re-establish the Fetter Lane Congregation at the Chelsea site in the 1960s. This is where the congregation has worshipped ever since, with the responsibility of looking after 'God's Acre', which contains the graves of such as Peter Böhler, John Cennick and James Hutton. There is a second burial ground in the Kings Road at Dovehouse Green. It was originally a gift from Sir Hans Sloane to the borough in 1733, for use as a burial ground, and closed in 1824. There is a plaque on the Green as a memorial to 457 civilians killed in WWII. It is also the burial place of Cipriani, the Italian painter and engraver, and the botanist John Martyn who introduced peppermint into pharmacy. It was laid out as a garden in 1977. |

Moravian Church |

|

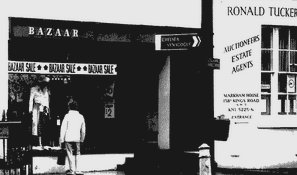

Property prices increased

dramatically, particularly at the east end of the road where a shop worth

£4,500 in 1950 was worth £30,000 in 1967 and £45,000 by 1969. Gilston Lodge,

a detached six-bedroom house with a garage right in the heart of Chelsea

was last on the market in 1958 when it sold for £5,000. It is now worth

in the region of £8.5m. The seeds of perception of the Kings Road as the 'new' epicentre of 'Swinging London' and British fashion were sown in 1955 with the opening of Mary Quant's 'Bazaar' shop, the event which seemed to be the catalyst for the increasingly rapid expansion of the 'boutique' and fashion design industry into West London. By the mid-Sixties it had become very much the place to 'see and be seen', an image which it has largely maintained ever since, and was also well advanced in shifting the 'Swinging London' title away from the narrow, seedier streets of Soho. Not only were the major entertainment and socialite personalities of the day increasingly taking up residence there but the migration and expansion of the Carnaby Street and Portobello boutiques, together with new names and some major 'foreign' fashion houses establishing a presence here in the UK, was taking advantage of this previously untapped market and 'fashion showcase' in the period from the mid Sixties to the early Eighties. Up to the mid-Fifties Chelsea was regarded as London's 'Bohemian' sector, or 'London's Greenwich Village'. Kings Road was just the local shopping and gossiping street for the area favoured for two centuries by those of a literary and artistic bent. The opening of Mary Quant's pioneering clothes boutique heralded the beginning of what were to become major changes. The little tea shops started to disappear under the influx of retail commerce and, by 1969, the half-mile 'fashion' stretch of the King's Road had over 50 assorted boutiques, with their loud music, brash frontages and garish fittings in complete contrast to the more reserved architecture of the older houses. |

|

|

All

Original Material Copyright SixtiesCity

Other individual owner copyrights may apply to Photographic Images |