|

|

|

| That wasn't

quite the end of it. On the second attempt, the 2" thick rope they were

using to hoist the cabinet began to fray and despite efforts to pull it

in at level one (about seventy feet above sea level) it got caught under

the edge of the platform on gun tower one. An attempt was made to run chains

through the cabinet's casing to support it, but to no avail as the cabinet

tilted and dropped towards the sea. Fortunately, the captain of the tender

had learned from the first attempt and had moved his boat away from the

tower. The rope holding the cabinet eventually parted and it fell into the

sea and sunk to a depth of about twenty feet, its position marked by the

frayed ends of the rope. Alex continues "That night, on our ship-to-shore link-up, Reg Calvert asked if anything went wrong and, I do believe, had a seizure on hearing the news that his £5,000 transmitter was lying in twenty feet of salty water. After he recovered he arranged for divers to come out next day and salvage the submerged transmitter". It was eventually retrieved with the assistance of local divers from The British Sub Aqua Club and hoisted onto the tower. Although some accounts claim that the equipment did not work after its unplanned swim, the unit was cleaned up and returned to operating functionality. However, due to its size, its power demand was much greater than the generators on the fort were able to supply for extended periods, despite the best efforts of Radio City and Caroline engineers, so it was put aside, with Radio City engineers Phil Perkins and Ian West modifying the original equipment to make it seem that the transmitter was operating at greater efficiency than its very low 2kW. DJ Ian Macrae commented "Radio City engineer Tony Pine told me that the transmitter never worked properly, not just because of the effect of sea water but because the generators weren't able to provide enough power to drive it. I recall we had to turn off all other electrical devices such as lights etc. when the big transmitter was running but the generator just wasn't up to the task. The engineers had warned Reg Calvert about this when he told them the transmitter was coming out but he just ignored the advice saying 'Find a way to make it work!'" When Project Atlanta sent Radio City the £600 invoice for the transportation costs from Texas, Reg Calvert refused to pay. He returned it to Atlanta saying that the transmitter did not work, was their responsibility and that they could come and collect it any time they wanted. This did little to help relations between the companies and the agreement was ultimately not a success. |

|

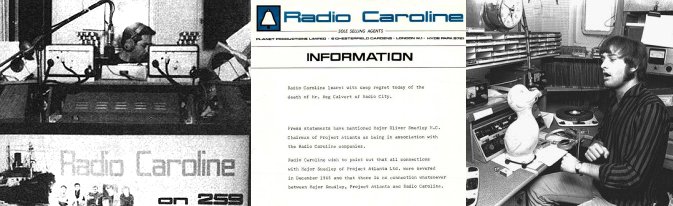

| All

the finances had been handled through Project Atlanta and, within three

months, Radio City was alleging that it was owed various revenues and operating

costs that had not been paid by Project Atlanta who ended up owing Radio

City something in the region of £8,000. Planet Productions took over the

assets and liabilities of Project Atlanta in December following which Allan

Crawford resigned from the board. Effectively, Project Atlanta had gone

bust and, at the end of December 1965, the owners of Radio Caroline North

(Ronan O'Rahilly's Planet Productions) bought the Radio Caroline South ship

too. It was believed that all connection with Atlanta's ex-chairman and major shareholder, Oliver Smedley, had been severed at this time but he was known to still be holding 60,000 Atlanta shares as late as 1972. With the 'fall of Atlanta', the agreement with Reg Calvert ended. Radio City returned to selling its own airtime advertising and paid its own operating costs again with effect from January 1st 1966, but the subsequent legal disputes carried on for months. Radio Caroline later claimed that it had severed all connections with Project Atlanta in December and that the provenance of the transmitter remained a matter for dispute. After a somewhat controversial career, Radio London finally really sacked Kenny Everett (he had been sacked and quickly reinstated several times previously) in October 1965 after he made irreverent comments about Garner Ted Armstrong, one of the station's main religious sponsors. Such was Kenny's popularity though that he was re-employed in June 1966 after a suitable 'cooling-off period'. Also in October, Radio London became a film star when the ship and crew were used for the storyline and location sequences in a feature film called 'Dateline Diamonds', released in 1966, with brief appearances by Phillip Birch, Earl Richmond and Ben Toney. |

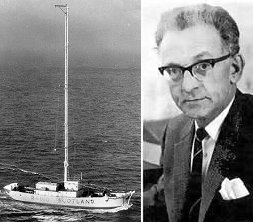

| New

Year's Eve 1965 brought another new station. After dropping anchor, rather

fittingly on Hogmanay, Radio Scotland commenced broadcasting at ten minutes

to midnight on 242 metres 1241kHz, 'Swinging to you on 242' from a converted

lightship off the east coast of Scotland 4 miles out from Dunbar in the

Firth of Forth. The opening announcements were made by television actor

and nouveau disc jockey Paul Young and Tommy Shields, the managing director

of its operating company City and County Commercial Radio (Scotland) Ltd.

which had been formed in October 1964. Being an ex-lightship, the 'Comet'

was effectively just a floating platform with no engines which had to be

towed everywhere. It was unable to operate its transmitter at full power until January 16th and soon after changed its frequency to 1260kHz. Radio Scotland had the distinction of being the only Scottish offshore station and was run by mostly local people, broadcasting a varied selection of programmes including ceilidh music and pop. January 1966 saw the end of the six-month life of land-based Radio Shanus. The transmitter was confiscated and 18 year old Martin Macgregor, who had started the station as part of a college rag week stunt, was fined £2. Martin adds "....and please do not forget the 3 guineas costs!" In the early hours of January 12th the Clacton lifeboat was launched to attend the Radio London ship 'Galaxy' which had dragged her anchor in a force 8 gale, ending up close to Clacton and necessitating shutdown of transmission while it was within territorial waters. The pirates, even in adversity, were never short of a sense of humour and the first record played on resuming programme transmission was 'Day Tripper' by The Beatles. |

|

|

The winter

conditions of that year caused many problems for the North Sea pirates.

Radio Syd ceased transmissions to Sweden on January 20th 1966 when it was

thought that pack ice caused by the severe Baltic weather might damage her

thin hull plates, so she had to move from her anchorage and, unable to return

to her former position, headed for the English coast On the evening of the same day, 'Mi Amigo' broke her anchor chain and started to drift, which went unnoticed by the crew who had finished broadcasting for the day and were apparently watching television below deck. The ship ended up aground on the Holland Haven beach near Frinton-on-Sea, having somehow avoided the multitude of concrete groynes which protruded all along that coast. Several staff had to be taken off the ship by breeches buoy, including Dave Lee Travis, Tom Lodge, Graham Webb and Tony Blackburn. Attempts made by the tug 'Titan' to pull her off were unsuccessful but the captain managed to kedge her off and refloat her on the 22nd following which she was taken to Zaandam in Holland for a damage inspection and repair. It looked as if the station was going to be off the air for quite some time, while repairs were carried out, until an unexpected offer of a replacement ship came from Britt Wadner. At the time it was widely reported that the 'Cheeta II' was being loaned free of charge but the rental was, in fact, charged at around £750 a week - cash! So, between 31st January and 1st May 1966 Radio Caroline South was broadcast from 'Cheeta II' which actually carried the first ship-borne television station with a UHF TV transmitter (using Channel 41) and an ingenious aerial system. The TV studio, including lighting etc., was in the hold and this is where the Caroline studio was set up. Radio Syd had, previously, normally broadcast to Sweden on VHF-FM but, at that time, this was a waveband not widely used in Britain so one of the 'Mi Amigo's 10kW medium wave transmitters was brought back from the ship currently under repair in Holland. It was installed by Caroline engineering staff who also rigged a makeshift aerial for the AM signal, but the low masts on 'Cheeta II' meant that the possible aerial array was not really up to the job, emitting sparks if high power was applied. Even so, 'Cheeta II's generators still weren't powerful enough to run the Caroline equipment so a General Motors 75 kV diesel alternator was brought back from the 'Mi Amigo' as well. As a result, Caroline was only able to broadcast from its temporary home at reduced power but at least ensured a continuing income from advertising. Night time reception was particularly bad so transmission hours were shortened. The station had been losing listeners to Radio London for a while and during this period wholesale changes to the broadcasting staff were made when Tom Lodge was brought in to revamp the operation. He gave the remaining disc jockeys a much bigger say in programme content and injected a new enthusiasm and more spontaneous style into their presentation by the time the 'Mi Amigo' started broadcasting again on 27th February from Holland, relaying through 'Cheeta II'. |

| In

March a proposed station called 'Radio Mayflower' announced that it planned

to start a service in April, transmitting from The Wash, near Boston. Throughout

1965 and January 1966, testing at Tower Radio continued to be problematical

but they finally settled on the 236m wavelength. On 5th March the station

ID was changed to Radio Tower and they announced on 24th March that it would

commence broadcasting on 21st April, 7am to 7pm. On 8th April a new generator

was taken to Sunk Head but was damaged during unloading. It was repaired

on land and returned to the fort on a fishing vessel called 'Venus'. A few

days after this their regular tender, 'Maarje', was impounded by Customs

& Excise for unpaid bills and later sold off. Radio Tower jingles were produced

at Martello Studios, run by Robin Garton, whose family owned the Martello

Holiday Park at Walton-on-The-Naze. Despite having attracted a 12-month advertising contract with News of the World magazine, Vision Projects were declared bankrupt on 28th April. Radio Tower continued to broadcast regularly until 4th May and then erratically, with their last transmission being heard on 12th May 1966. Also during April 'Radio Channel' was believed to be preparing to broadcast from off the coast of Bexhill, Sussex, and a station called 'Radio Dynavision' was heard, but as very little else materialised after that it may have only been a test transmission. Yet another short-lived transmission in May identified itself as 'Radio Jim'. On April 22nd, because of the frequently adverse weather conditions and poor mainland signal reception being experienced by Radio Scotland, an operation began to transfer 'Comet' to a new position three miles off Troon on the west coast. The ship continued broadcasting programmes as it was towed for the best part of a thousand miles around the north of Scotland. They could hardly have picked a worse time of year and the voyage was horrific. There were storms, a fire broke out in her generator room while she was off Peterhead and, at one point, she was shipping so much water that her own pumps couldn't cope and they were forced to request someone to send an extra pump by making an appeal during programme transmissions. |

|

|

The twin

stations, both operating from the same ship, were created by some of the

Texan backers who had broken away from Radio London to form Pier-Vick Ltd.

which consisted of Don Pierson, Bill Vick, general manager Jack Curtiss

(grateful thanks to Jack for providing information corrections) and programme

director Ron O'Quinn. The twin-studio ship was originally a World War II

Liberty Ship named 'Olga Patricia' that had been refitted, renamed 'Laissez

Faire' and was anchored three miles off the coast of Walton-on-The-Naze. During World War II, 2711 of these ships were built in US shipyards and saw action in the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, the Indian Ocean and the Pacific but were probably most remembered for their participation in the dreaded 'Russian convoys' through northern seas past Norway to the Russian port of Murmansk. Their lack of speed made them an easy U-boat target and about 200 were lost through enemy action. Their expected life span was a mere five years but, even so, such was the likely casualty rate that the Navy considered one safe voyage to be a ship's full quota. During the early part of 1966 an audience survey was commissioned from National Opinion Polls Ltd. by Brian Scudder, the sales director of Radio Caroline. The company reported that during the period of the survey about 45% of the population listened to Luxembourg or offshore stations. The listening figures (as reported) were: Radio Luxembourg - 8,818,000, Radio Caroline - 8,818,000, Radio London - 8,140,000 Radio 390 - 2,633,000, Radio England - 2,274,000, Radio Scotland - 2,195,000, Britain Radio - 718,000 (In June 1967 National Opinion Polls published more figures showing that Radio 270 had an audience of 4.5million). Radio England, initially on 355 metres 845kHz, changed to 227 metres 1320kHz after complaints of interference from Italy. At one point, the numbers 227 were clearly visible on the bows, but not in the image shown. More vehement complaints of interference, received on June 3rd from Radio Roma II, resulted in it reverting to its original wavelength and frequency. Its weekday output consisted of non-stop pop and chart music using experienced American disc jockeys with their own style of broadcasting, the weekend being largely devoted to 'golden oldies'. Because of its (to British listeners) unusual American broadcasting style it failed to attract advertisers (as was the fear of Radio London) and was less successful than it really deserved. Britain Radio on 227 metres 1320kHz was more middle-of-the-road easy listening in style. |

| During

April 1966 Radio London and Managing Director Philip Birch had started to

negotiate their own proposal with Reg Calvert for 'Big L' to take over the

fort's operation in order to launch an 'easy listening' station to rival

Radio 390 and the Britain Radio stations. This may also have been part of

another project rumoured to be in the planning stage called 'Radio Manchester'

which was to be a sister station for Radio London. Similar to the Radio

Caroline idea, it involved finding an alternative base for the south-east

radio station so that the 'Galaxy' could be moved and anchored off Fleetwood,

Lancashire, to serve the north-west of England. A joint sales company was proposed, comprising Radio London and a new one, UKGM (United Kingdom Good Music), with a servicing and tendering agreement shared between the two stations, Radio London to manage the operation and receive 55% of the advertising revenue while Reg Calvert received 45% and retained ownership of the tower. A draft agreement was drawn up in May that proposed the setting up of a management company to be called 'Sweet Music', to be jointly owned by Reg Calvert and Radio London, which would operate a new station to be called 'UKGM'. It was planned that the agreement would come into effect on 1st June with UKGM becoming fully operational on 1st July. Plans for the launch of UKGM were first announced to the public in a newspaper article on 16th June but did not proceed quite as envisaged. Radio London disc jockeys Keith Skues and Duncan Johnson were given the task of overseeing the programming of the new station and, together with engineer Martin Newton and Radio London office manager Dennis Maitland, visited the fort in early June 1966 to inspect the facilities and technical standards in order to get a better idea of what was going to be required. They were not overly impressed with either and subsequently raised questions about its suitability. While the negotiations with Radio London were taking place it seems that Reg Calvert was simultaneously holding clandestine discussions with Major Oliver Smedley of Project Atlanta who was offering to either buy the station outright for about £10,000 or issue him with the equivalent value in shares for the formation of a joint operating company. Smedley was keen to get in on the business, especially as he was still owed the money for the radio transmitter he had supplied. There is a story that he visited the Radio City offices with a 'Mr. Fablon' to view their accounts on behalf of an anonymous potential buyer. Calvert was loath to commit himself at that point, still being in discussion with Philip Birch, and nothing came of this particular incident or the negotiations in general. When Smedley learned that Reg Calvert had agreed to go into partnership with Radio London he became concerned that there might be a danger of him completely losing the value of his transmitter investment and decided to take more direct personal action. This saw the start of a dark train of events which was to scandalise pirate radio. A few days before the Radio London agreement became due to be signed, Oliver Smedley advised Atlanta's Allan Crawford of his intention to board the fort and repossess the transmitter. Crawford refused to get involved in the plot and tried to advise Smedley against it, forbidding Smedley to associate Project Atlanta with the plot should he go ahead with it. Dorothy Calvert, Reg's wife, apparently received a telephone call from Ted Allbeury, the boss of the rival Radio 390, who had heard rumours that someone was plotting to take over Calvert's fort by force. Oliver Smedley assembled a group of about ten riggers and Trinity House pilots (led by 'Big Alf' Bullen) who were, at that time, out of work due to the London Docks strike and, along with Dorothy 'Kitty' Black (one of the original Project Atlanta shareholders), sailed from Gravesend Pier around midnight on Sunday 19th June, arriving at Shivering Sands tower at about 3.30am. On Shivering Sands, Radio City had closed down for the night and its complement of ten (reports vary between seven and ten) staff were asleep as Smedley and his group boarded the fort in darkness. Little or no resistance was offered as the staff were locked up by the boarding party. Smedley's team proceeded to remove the station's transmitter crystal, preventing the station from broadcasting. After a few hours Smedley, Kitty Black and some of the group returned to the mainland, leaving behind an 8-man occupying force to oversee their 'prisoners'. At the usual start of airtime at 6.00am on Monday 20th June Radio City was silent. |

|

|

On their return to the mainland Smedley and Black drove to Philip Birch's

home in Kent and invited him to attend a meeting, later in the day, that

was to be held at Project Atlanta's offices in Dean Street, Soho. Birch

advised Reg Calvert about the meeting but Calvert was late arriving. It

proved to be a rather heated affair, attended by Philip Birch, Oliver Smedley

and other Project Atlanta shareholders including Kitty Black, Horace Leggett

and Captain Sandy Horsley. Smedley announced that he had taken possession

of the fort and wanted a share of the deal with Radio City to remove the

boarders and compensate him for his transmitter. Calvert arrived shortly

afterwards and Smedley made the same offer to him as he had to Birch. Reg Calvert bluntly refused and demanded that Smedley remove the boarding party immediately, threatening to take it back by force if necessary and allegedly threatening to use nerve gas. Smedley responded by claiming that the men on the fort were armed and would destroy all the equipment if anyone tried to regain control. Philip Birch accused Smedley of blackmail, told him that he was not doing any business under duress and walked out, so the meeting broke up abruptly and angrily after about 15 minutes. Philip Birch subsequently announced that Radio London would not be going ahead with the UKGM proposal as his company operated in a legal and ethical manner (even though they were technically operating an illegal radio station) and would not get involved in this sort of business. On Tuesday 21st June, Calvert reported the boarding action to the police and asked for their help, although there was some uncertainty as to what could be done to assist. The occupying force, at some point, allowed a change of crew and also agreed to let themselves and the Radio City staff be interviewed by police but, as they were outside territorial waters and mainland jurisdiction, the police stuck to their view that there was nothing they could do to resolve the situation. |

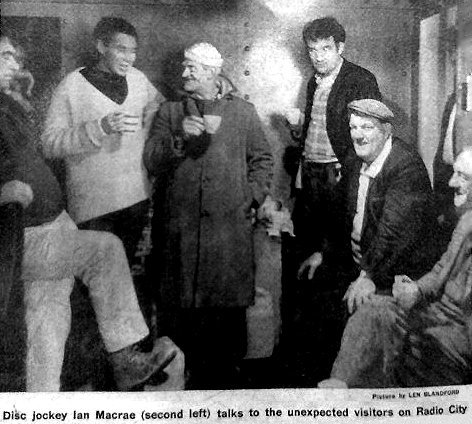

| Senior

DJ Tom Edwards, who was going out to the fort as part of the crew change,

recalled "I went out to Radio City knowing the raiders were still there.

They were polite although 'rough' characters. I was a young man and could

'strut my stuff' but yes, of course I was frightened". "Then the

news came that Reg had been shot. For goodness sake, I had only been with

him the day before in London and yes, he was 'wound up' ......... it's news

that didn't sink in at first. There were police officers and newspaper reporters

everywhere, both on and off the fort. The raiders were not happy and Big

Alf, who seemed to be in charge, said to me that he didn't know anyone was

going to get killed". On Sunday 26th June, a week after their arrival, the members of the boarding party still on the fort departed for no obvious reason, arriving at Sheerness just before midnight. On the fort a spare crystal, hidden from the intruders, was located by the Radio City staff and quickly used to repair the transmitter, resulting in radio transmissions being tested by 9.30pm and Radio City being heard again at 10pm with Ian Macrae being first on and playing, appropriately, 'Strangers in the Night'. Reg Calvert was buried on 1st July 1966 at St. Peter's, Dunchurch, with Screaming Lord Sutch and members of the Pinkerton's Assorted Colours pop group among the mourners. Major William Oliver Smedley was officially charged with murder on July 18th and his trial opened at Chelmsford assizes on October 11th where the charge was subsequently reduced to manslaughter. Smedley claimed that he was afraid that Calvert had come to kill him and claimed innocence on grounds of an action of self-defence when Calvert picked up a 'weapon'. A day and a half later, the jury agreed that he had acted in self-defence and returned a verdict of 'not guilty' without even retiring. |

|

|

|

All

Original Material Copyright SixtiesCity

Other individual owner copyrights may apply to Photographic Images |