|

|

|

|

Government concerns stated by Tony Benn, Postmaster General (64-66) and

Minister of Technology (66-70) included: 'The principal reason for taking action against the pirate stations is that they cause intolerable interference to the operation of broadcasting services in other countries and of certain maritime radio communication services in this country and abroad' (4th Feb 1965) 'The interruption of any of the authorised channels of communication between ships and the shore constitutes a danger to shipping. This was illustrated by the incident on 23rd February last, when a lightship was prevented for about 30 minutes from passing an urgent report to the shore because both of the frequencies available were blocked, one of them by a pirate broadcasting station' (22nd March 1965) and, on a different tack: 'They are also stealing copyrights of all records they broadcast and stealing the work of those who have made the records and the legitimate business claims of those who manufacture them'. However, in response to this, Johnnie Walker claimed that 'the pirate radio stations had always offered to pay royalties but the record companies refused because they didnít officially recognise our existence'. |

| David Lye

and Ted Allbeury appeared before three magistrates at Longport Magistrates

Court on November 24th. Radio 390 had already closed down, Ted Allbeury

having sent a taped message to the station saying "Hello there, this is

Ted Allbeury speaking. I cannot believe that this is the end. I am advised

that it might take three or four weeks for an appeal to be heard. If we

win, we would start broadcasting again immediately. However, if we lose,

it would mean that we should have to cease broadcasting from the fort. I

should expect to make some alternative arrangements. For now, all I can say is what I have always said - take care of yourselves and God bless". This was transmitted by DJ Steven West who then announced "We are now closing down". The national anthem was broadcast and the 390 wavelength went silent. After two days of debate and presentations on the location of the fort, Estuary Radio was found guilty and fined £100. However, an application by the G.P.O. to have their equipment confiscated was rejected and the two men were given absolute discharges. After a five-week closedown due to court proceedings Radio 390 returned to the air on December 19th (accounts differ as to the actual date) with the record "This Could Be The Start Of Something Big" and an announcement by Ted Allbeury "It's great to be back on the air and, furthermore, we shall stay on the air this time. We have new evidence that the fort is at least a mile and a half outside territorial waters. The survey was executed in accordance with Admiralty practice and the G.P.O. will have to summons us again if they feel they have a case". This statement was based on a hydrographer's findings that Middle Sands was 'always covered with water at low tide', technically making Red Sands Fort outside UK territorial broadcasting limits, but the authorities were apparently determined to get them by fair means or foul....... |

|

|

The Post

Office provided evidence that they had monitored transmissions from three

locations: Herne Bay, Shoeburyness and the Isle of Sheppey on 16th August.

It was also confirmed that Roy Bates had made an application for a licence

to broadcast but, as with Radio 390, this had been refused. Despite Bates'

continued insistence that the structure was outside the jurisdiction of

the Court because it was located more than 3 nautical miles off the Essex

coastline, the magistrates ruled in favour of the prosecution. They imposed

a £100 fine but refused a request by the Post Office to confiscate his transmitting

equipment, pending appeal. Advertising contract income had all but disappeared following the issue of the summons in September and, with insufficient money to continue operating the station or pay the staff, it only continued for a few weeks, closing down at around 4.30pm on Christmas Day 1966. The subsequent appeal was heard on 17th January 1967, but failed. Some of the transmitting equipment was dismantled and removed to Roughs Tower, which was off Felixstowe and outside territorial waters by any definition. Unaware of Bates intended relocation, Radio Caroline engineers boarded Roughs tower in January and, with the intention of converting it into an offshore supply base for the ship, started cutting sections of the superstructure away to allow helicopters to be able to land on the main platform. Roy Bates was quite irate at this and yet another series of skirmishes followed, ending with Bates regaining occupation of the tower, but no further radio station broadcasts ever became evident. Also see Pirate Forts, Roy Bates and Sealand On February 8th Dorothy Calvert's appeal, that Shivering Sands was situated in international waters, was also rejected by magistrates and she was fined £100. That night, at the end of normal transmissions, Radio City played 'The Party's Over' followed by the national anthem and disappeared forever into the pages of pirate radio history. |

|

Even after her trek to the west coast, Radio Scotland had not found the cure for her problems. On March 13th she was found to be within territorial waters 'in the Firth of Clyde near Lady Isle' and Tommy Shields' company was fined £80 for operating without a licence. Following this, preparations were made to take her to yet another new position back on the east coast off St. Abb's Head in the Firth of Forth but this was to be delayed due to bad weather. Once the tow was finally started they were again beset by storms which forced them to take refuge in Loch Ewe. Throughout this period Radio Scotland was losing money through lack of airtime advertising. The directors of City and County Commercial Radio made the decision not to continue with the east coast relocation and moved 'Comet' to a position off the Irish coast near Ballywalter, Co. Down, instead. Even there, the bad weather followed her and forced her to take temporary shelter in Belfast Lough. On April 9th at 12.31pm the station finally recommenced transmissions after four weeks of silence with its name changed to 'Radio Scotland and Ireland', alternatively known as 'Radio 242'. In the meantime, the second reading of the 'Marine Broadcasting (Offences)' bill had taken place on March 16th. This was almost simultaneous with an announcement from the Postmaster General regarding the government's plan to provide a popular music programme on national radio by the end of the year, which seemed to be merely a poor attempt at sugar-coating a very bitter pill for the listening public. Twenty eight further summonses were issued by the Post Office (which was the government department responsible for broadcasting licenses) against Estuary Radio on 13th February. The proceedings were heard by Rochford magistrates on 22nd February when Ted Allbeury, David Lye, Christopher Blackwell, John Gething, Michael Mitcham, John LaTrobe and Estuary Radio were accused of broadcasting without a licence on four days in January. |

|

|

The

Estuary directors were found guilty, with each being fined £40 and the company

£200. After this action, Ted Allbeury resigned from the board and David

Lye, took over. This was followed by another High Court action in May, but

Estuary Radio was given permission to appeal, and the case was postponed

until 28th July, allowing the station to stay on air in the meantime. Peir-Vick, the operating company behind the two stations aboard the 'Laissez Faire', had gone into liquidation on March 18th and it was taken over by the new company headed by Ted Allbeury, called 'Carstead Advertising'. The stations on board were immediately renamed, with Radio Dolfijn becoming Radio 227 and Britain Radio becoming Radio 355. With all these grim happenings, the offshore radio pirates could have been forgiven for losing their sense of humour. However, this was certainly not the case at Radio London who made spoof transmissions on April 1st, ostensibly from a (fictitious) station called 'Radio East Anglia' which they pretended was trying to take over their frequency. The spoof station disappeared suddenly at midday when they 'regained control'. Radio Scotland and Ireland had wanderlust again at the end of April. Their transmitter signal strength was not great enough to reach Scotland properly and so the return to the East coast was finally undertaken. 'Comet' and her towing ship 'Campaigner' reached the new anchorage at Fife Ness on May 8th by which time Radio Scotland had not only lost about £15,000 in advertising revenue but also incurred the tow and supply costs as well and was in a precarious financial position. |

| In between

these two events, Radio 390's final appeal was heard on 28th July and, not

surprisingly, the station lost when Lord Justice Sellers upheld a decision

by Justice O'Connor ruling that the Red Sands fort was inside territorial

waters and was operating illegally. That evening, at 5pm, Graham Gill read

a news bulletin which was followed by a pre-recorded edition of the station's

only pop programme 'On the Scene' presented by Christopher Clark. After

just one record, the news of the court verdict reached the station and the

show was interrupted for a pre-arranged message to be broadcast by senior

announcer, Edward Cole. Then, after playing the Alan Price record 'The House

That Jack Built', followed by the national anthem at 5.10pm, there was nothing

but silence on 390 metres. The staff on Red Sands, in expectation of the eventual closure, had been working on a closedown programme, but the instructions they received from directors at head office were to close immediately, so it was never heard. Engineer Laurence Bean switched off the transmitter and he and the broadcasting staff departed on the tender boat. The tapes for the pre-recorded final show were somehow left behind on the fort, to be discovered some time later, and copies were circulated among fans of offshore radio. Around the same date a decision was made to close Radio London down. Perversely, the demand for commercials increased near the end as companies took advantage of the last opportunities to get advertisements for their products on the air. As previously noted, the final 'Fab 40' on Sunday 6th August contained 18 records that had not yet even been put on general release. |

|

|

At

10pm on Saturday August 5th Radio 355 followed its sister station into

oblivion when operating contracts expired. All the station's disc jockeys

joined Tony Windsor as he chaired the final programme to be broadcast.

Following an advert for 'Silexene' paint, Tony Windsor spoke for a while

then handed over to station owner Ted Allbeury who made a short speech,

ending with the final words ' . . . goodnight and God bless'. A recording

of 'Auld Lang Syne' followed and Radio 355 disappeared from the airwaves

to the sound of the national anthem at 21 minutes after midnight. It has

always struck me as being quite poignant how many of the stations, despite

their various origins, were to close by playing the national anthem of

the country that was so keen to destroy them. |

| Radio

270 closed down officially at 23.59pm. Strangely, their final shutdown had

nearly occurred 24 hours earlier than planned when transmissions were interrupted

by an overheating generator caused by a shoal of giant jellyfish being sucked

into the cooling system's seawater intakes. It was originally intended that

the entire DJ team should be on board for the final show, but rough weather

prevented the tender setting out so, at the end, the ship only had three

broadcasters aboard who had to handle the last 20-odd hours of programmes

between them. The staff stranded on shore recorded farewell messages but there remained the problem of how to get them out there. Against all the rules, Deputy Programme Director Mike Hayes persuaded a friend in the R.A.F. to drop them by helicopter, together with a note that no mention of this should be made on air. In short, the package missed the boat but the DJs saw the helicopter fly past. Thinking it was just a farewell visit, they said thank you on air, which led to some difficult questioning when the pilots returned and was, apparently, even commented on in Parliament. With their tapes in the sea, the final hours were broadcast by the station's programme director Vince 'Rusty' Allen who played every single one of their jingles and theme tunes. Various other recordings and telegrams from the station's management were heard before the final record, Vera Lynn's 'Land Of Hope And Glory'. Rusty Allen then signed off emotionally, with the words 'God bless and God speed. Goodnight and goodbye - Radio 270 is now closing down' and finally closed the station to the sound of the national anthem. The 'Oceaan VII' sailed into Whitby to a hero's welcome the following day and, despite nearly becoming the next incarnation of Radio Caroline in 1968, the twin-studio ship was eventually broken up for scrap. Its transmitting equipment was removed and put into storage, subsequently being transferred to the vessel m.v.'King David' that was to be the home of a pirate station called 'Capital Radio' which broadcast from off the Dutch coast in the early Seventies. Final 10 minutes of 270 |

|

Radio

London hung on until the next day. Professional to the last, the final hour

had been pre-recorded to avoid the possibility of emotions taking over,

closing with 'A Day In The Life' by The Beatles followed by the voice of

disc jockey Paul Kaye saying simply 'Big L time is 3 o'clock and Radio London

is now closing down'. The 'Big L' jingle was played, after which staff member

Russell Tollerfield switched the transmitter off for the last time.

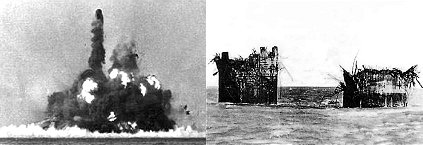

Radio

London Closure At, or slightly after, 3pm Robbie Dale of Radio Caroline gave a eulogy for Radio London and observed a minute's silence. The 'Galaxy' was towed to an anchorage on the German North Sea Canal where it was eventually sold to the German advertising agency Gloria International. On August 21st the destruction of the offshore forts was begun by the M.O.D. to prevent any further use by private individuals. Sunk Head was the first to go when over 2,000lbs of explosives were detonated at 4.15pm, watched by Roy Bates from Roughs tower, six miles away. The Marine Broadcasting (Offences) Act was reluctantly ratified by the Manx Parliament on August 31st at 8.30pm, to become effective at midnight. Although now subject to prosecution, Radio Caroline North stayed on the air and at midnight disc jockey Don Allan's voice was broadcast saying: "This is the northern voice of Radio Caroline International on 259 metres, the continuing voice of free radio for the British Isles". With the threat of prosecution now a reality, the personnel on the South ship had already changed dramatically, the only remaining disc jockeys being Johnnie Walker, Ross Brown, Spangles Muldoon and Robbie Dale. They were later joined by more disc jockeys of other nationalities, but during August and September the ship operated with a skeleton staff. |

|

|

The Radio

Caroline North ship was now supplied from Dublin in Eire and the South ship

received its supplies from Ijmuiden in Holland. On 26th September the station

reduced its broadcasting hours, closing down between 2am and 5am due to

the overworked disc jockeys being unable to cope with a 24 hour schedule.

Four days later BBC Radio 1 was heard for the first time. On the day it went live the Radio Caroline South ship encountered technical problems which made it impossible for them to use live transmission, only being able to play pre-recorded tapes. In December 1967 Radio Syd was granted a broadcast licence in The Gambia, transmitting from a land-based facility on 329 metres 910kHz. The 'Cheeta II' was sold in 1971 but partly sank in a storm during August of that year. Both Radio Caroline International ships continued as normal until Saturday March 2nd 1968 when the Dutch tug 'Utrecht' anchored about a mile away from the Caroline North ship and refused to acknowledge any attempt at communication. Don Allan's show, after playing 'God Be With You Till We Meet Again' by Jim Reeves, finished at 10pm as usual and the ship settled down for the night. At about 2am on March 3rd crewmen from the Dutch tug boarded the ship, disabled the transmitter and held all the crew and staff in captivity. Similar events were also occurring on the Caroline South ship where they had already started the day's programmes when crew from the tug 'Titan' boarded her just after 5am. Equipment was ripped out and the station went off the air, without any warning, in the middle of a record. As with Caroline North, the transmitting crystal was removed and the crew of 'Mi Amigo' were imprisoned. |

|

The ships had been seized by the Offshore Supply Company in lieu of £30,000

unpaid debts for their services and were towed to Amsterdam where the crews

and staff were released and sent home to England. Despite the earlier threats

from the British government, none of them were prosecuted on their return.

Shortly afterwards the vessels were moved to a mooring in the Verschure

shipyards. That was, effectively, the end of Radio Caroline International

as a pirate station in the Sixties, but Ronan O'Rahilly didn't give up quite

that easily. However, it would take four years for the station to return to the airwaves. In the intervening years, Caroline would be heard only twice - a one hour 'commemorative' show on the foreign station Radio Andorra on March 2nd, 1969, from midnight until ten minutes past one, and in 1970 when the 'Mebo II' RNI station transmitter was used in the 'revenge' campaign to back the Conservatives during the British elections because of its history and familiarity to the British public. Almost exactly one year after the Broadcasting Offences Act came into effect a station called 'Radio London Three' transmitted for about an hour on 204 metres as a protest against the Act. Over the next few days the station changed its name to 'Radio Free London' and was heard intermittently. The signals were finally traced to a flat from which ex- Radio Caroline disc jockey Spangles Muldoon (alias Chris Carey, who was later to become the head of Radio Nova) was broadcasting. Others involved in the operation were Dick Fox-Davies, DJ Brian James and an un-named G.P.O. engineer. The radio transmitter was dismantled and confiscated but the ex-pirate had the last laugh. The equipment that was taken was a false set-up and the actual working transmitter was left intact! |

|

| Capital

Radio was formed by the International Broadcasters Society on August 23rd

1969 who then proceeded to buy and refit the 360 ton coaster 'Zeevaart',

renaming it 'King David'. The ship had a unique lateral circular aerial

(which caused them a lot of problems) and was equipped with the transmitter

salvaged from Radio 270. Capital Radio made its first test broadcasts, using the same 270 metre wavelength, on May 1st 1970. It was not until 1973 that licensed commercial radio stations eventually appeared in Britain. The last of the legendary Sixties offshore pirates still operating in its original form, Radio Veronica, finally succumbed to the 'Dutch Marine Broadcasting Act' on August 31st 1974. The last half-hour of disc jockey Rob Out's show featured a clock ticking loudly in the background. There was a news bulletin at 5.30pm followed by the owner, Bul Verweij, until 6pm when Rob Out took the chair to sign off with the epitaph "This is the end of Veronica. It's a pity for you, for Veronica, and especially for democracy in Holland". These final few words were followed by the Dutch national anthem and a station jingle, which only got halfway through before the signal . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

|

|

At 02:30 on 11th September Mi Amigo ran aground on a sandbank. Holed in two places and 6ft deep in water, broadcasting ceased and the Dutch crew members were taken off the ship. On landing at Ostende, they somehow located an anchor and chain aboard an impounded oil tanker and appropriated it for use on Mi Amigo. The ship was towed off the sandbank on 16th September. On 18th January 1979 the Mi Amigo sprang a major leak, issuing a 'mayday' on the following day which was received by the Thames Coastguard. Three vessels ('May Crest', 'Sand Serin' and 'Cambrai') were sent to assist. The ship had to be abandoned but was later re-boarded and salvaged. On 19th March 1980, Mi Amigo's anchor chain broke again in a Force 10 storm. After drifting for 10 nautical miles she eventually ran aground on the Long Sand Bank. At 23:58 a final broadcast was made by DJs Stevie Gordon and Tom Anderson, following which the Sheerness Lifeboat took off the 4 crew and a canary!. Mi Amigo sank on 20th March, leaving only her 127ft mast above water. On 22nd May plans to refloat the ship and turn her into a museum ship at Ramsgate were announced by Thanet District Council but the ship remained as a sunken wreck. Her mast eventually collapsed at the end of July 1986 and, on 13th September, it was decided that the position of the wreck, lying in 8ft to 16ft of water, was to be marked by a buoy. All At Sea (part 1) - The story of offshore pirate radio in the 1960's presented by Ray Clark. Broadcast on 'Pirate' BBC Essex Easter 2004 All At Sea (part 2) - The continuing story of offshore pirate radio presented by Ray Clark. Broadcast on 'Pirate' BBC Essex in August 2007 When Pirates Ruled The Waves - The story of offshore radio, written and presented by Paul Rowley for BBC Radio Shropshire |

|

|

All

Original Material Copyright SixtiesCity

Other individual owner copyrights may apply to Photographic Images |